I am a Chinese intercounty (International), transracial adoptee. I reunited with my biological family five years ago, going on six years soon. Some days it still feels surreal and other days it feels like I have always known them.

Six years ago, if you had asked me when my birthday was, I would have said December 5 with an uncomfortable feeling; a painful reminder of my unknown past. Now I answer the same question with a pause, wondering whether or not to share that my birthday is July 16. If you had asked me six years ago how many siblings I have, I would have said half the number I now know to be true.

As a child, and even in my teenage years, I was told (and believed) that if I was still in China, I probably would not have made it through school. I would not have the same opportunities I have in America. I might have been hidden or, even yet, may not be alive. I would not have had access to some of the medical care I needed. I was told that being deaf, I would have been rejected by society. I would have been poor, simply because my family was assumed to be poor, and I would not have a “successful” or “happy” life. I wrestled with this supposed “truth” and “luck” I had over the years.

The questions I had and beliefs I held continuously changed through different seasons of life. I did not have the language to express the complexities of my thoughts, and I did best when all of my feelings were tucked away and hidden. Sometimes, I could only hold anger because there was no other identifiable feeling. I often became numb and would find myself conforming to the statements around me: “lucky”, “chosen”, “grateful”, “fortunate”, “blessed” and so on. I would agree with a smile, though internally I did not necessarily concur with these beliefs. In other seasons of life, I missed, grieved, and carried the weight of these many ambiguous losses alone.

The experience of the unknown often leaves uncertainty, anxiousness, fear, and confusion. As a child, the unknown and undisclosed were not concrete thoughts or information. The inconsistent answers about my birth parents and my past were all I had to make sense of why I was here. My understanding of my past was based on many different theoretical situations, intentional/ unintentional assumptions, and imaginary scenarios of what might have possibly happened. There were a few documents containing almost no helpful information. Not even my birthday was known to be correct.

These unknowns also impacted how I viewed myself. It made me wonder what my parents looked like, especially when I saw friends with their parents. It made me wonder about concepts such as nature vs nurture. At doctor appointments I would watch again and again as a long diagonal line would make its way across the medical history forms, followed by the word “unknown” written across the documents. In school I remember learning about China during history class. I would always feel every pair of eyes glancing towards me as the only Chinese student. I could feel part of me wishing I was connected to what I read and shame for not having that connection. Learning about genetics and family trees in school would only reaffirm the unknowns, and this time to teachers and classmates with whom I wasn’t always comfortable sharing.

As a child I remember fantasizing about reuniting with my birth mom (though rarely imagining my birth dad). For the most part, when I imagined my birth mom, her face was blurred, and yet I found comfort in simply imagining her. I imagined her holding me during days and nights, especially when I was sad. I would imagine her saying, “I wanted you… I never wanted to give you up…I love you.” One of my favorite childhood movies was The Parent Trap (with Lindsey Lohan). I would creatively hope for all the possibilities of running into a sibling or even a twin, just like in the movie.

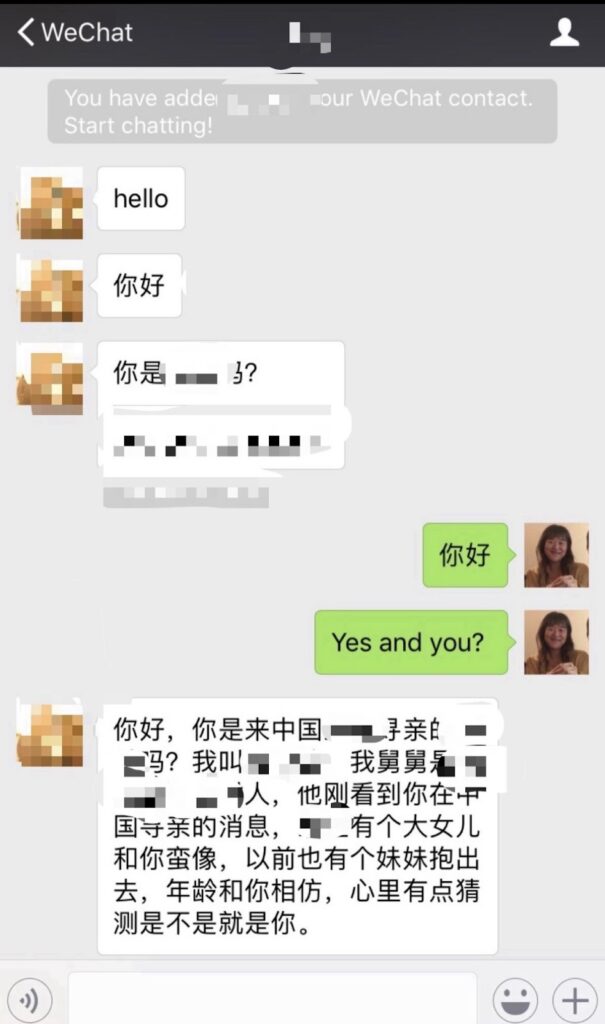

I can still remember the day that I received a text from a biological cousin. It was March 31, 2018. Next, my biological brother Yujie texted and then my biological sister, Jianfei, did as well. Seeing their photos and exchanging messages through WeChat/Weixin (China’s messaging/social media app) was indescribable.

Let me rewind a few months. In January of 2018 I was looking over my 23andMe account. I’d had the 23andMe account for a year and every few months I liked to click on “DNA Relatives” to see if any new close relatives were added. Up until January 2018, the closest biological relatives I was aware of were 4th cousins. This time I noticed I had a new DNA match with a 3rd cousin. We shared 0.53% DNA to be exact. Despite that not being a significant amount of shared DNA, I decided to reach out to this cousin. Surprisingly, my cousin was an international student from China. We exchanged multiple text messages. I also connected with her mother, my Ayi (阿姨). Ayi was determined to find my biological family. She asked some of her family who resided in a village near the city of my orphanage. Initially Ayi thought she had found my family: a father who worked in a factory, a mother who stayed at home, and a daughter who was already married. The only information I had to offer was where I was taken after being found and an estimated birthday. This information was an estimate but enough to know this did not match that of their lost daughter. I had been through this type of situation already and at this point grieved more for this family than I did for myself.

Ayi was steadfast in her quest to find my biological family. She reached out to a well known news reporter, and he agreed to write an article about me. During our interactions on WeChat, I called the news reporter Uncle Zhou (周叔叔). Uncle Zhou formulated the article and uploaded it on 12-15 different news websites. According to Uncle Zhou, in the first two to three weeks alone, over 15-18 million people read the article. While 15-18 million people is an astounding number, it was minute compared to the 57.37 million people who lived in the province, and the 1.4 billion people in China. Ayi was able to contact the “prefecture-level city” where my orphanage was located. The following days a few people contacted me to share that they read my article and wanted to assist with finding my biological family. Another person reached out as well, convinced that we were siblings because he felt we looked alike. We messaged for days, though at the end the information did not align and I had a gut feeling that he was not my brother.

One month after the article was posted, I received an unexpected message from a supposed cousin (my father’s sister’s son). He soon after shared the contact information for my potential brother and sister. Around a month later, my parents and I finally connected on WeChat.

For almost two months we exchanged photos, briefly recorded videos, and messages. I felt 99% sure that this was my biological family. In May of 2018, DNA results were confirmed. My family was found!

For a little over 20 years My ba (吧) and ma (妈) believed that I was still in Zhejiang Province, only a few hours away from them. It was evidently shocking to them that I was 6,500 miles away in the United States, a fact they learned for the first time when they came across my article. I was in awe of the opportunity to find and connect with my birth parents. I was also elated in gaining two siblings: Yujie, my brother (弟弟) and Jianfei, my sister (姐姐).

Since finding my birth family I have had opportunities to video chat, message, and reunite in person with my parents and siblings. In midst of the deep gratitude and thankfulness, there are also complex feelings and multiple layers of multidimensional loss, grief, shame, pain, cultural differences, and language barriers that are continually navigated. We have since shared some tears and even more laughter. There have been seasons of daily contact and other seasons of weekly contact. We have had many conversations and learned to appreciate each other’s presence without words. My sister and I continue to share a special relationship. We share a mutual understanding of some similar experiences in our lives. I am very thankful I have known her through her singleness, dating, marriage, and now having a son. My brother and I have similar personalities: caring, reserved, peacekeeping, and thoughtful. We share a mutual enjoyment for basketball, food, boba, and outdoor adventures. I appreciate our exchange of conversations through WeChat and his sincere check-ins.

Though it’s an “Asian thing” to rarely say “I love you”, I have witnessed and grown to understand the love of my ba and ma through their care, worry, and their quality time through video calls. They take time to check in with a message of “how is work?” and “are you healthy?” and “Don’t eat too much fried and spicy foods.” and “dress up… wear nice clothes…Find yourself a boyfriend” (*Currently rolling my eyes on this comment*). The times we have been together in person consist of parties, family gatherings, outdoor adventures, shopping, appreciating village life, spending time together, and learning the necessary chores and some cooking. The relationship with my birth family has evolved and continues to evolve into one that has grown with learned trust, grace, and forgiveness.

Personally, my reunion brings both waves of both and bursts of sadness. It brings both hurt and healing. It brings a sense of closure and a thousand more questions. It brings concreteness to ambiguous loss. It gives me a greater understanding of the beauty of my people and the brokenness of my birth country. It allows me to further understand and grieve the actions that occurred to my parents and me. The connection with my birth family permits opportunities to process and forgive in ways I had not yet done. It broadens and changes the perspective of how I view my past and the first chapters of my story.

Meeting or reuniting with a biological sibling, parent, uncle, aunt, cousin, or grandparent brings a broad spectrum of emotions for each adoptee who experiences a reunion with a family member. Adoptees might describe reuniting with family members as surreal or even as a nightmare. Being reunited can be filled with moments that will forever change their lives. It is complex and while it can bring closure, it can also provoke a collision of fear and courage, heartache and happiness. Sometimes it allows an adoptee to feel relieved and other times, confused. Reunions often provide answers and clarity to the past unknowns. For intercountry and transracial adoptees, there can be cultural differences and language barriers. Reunions can create at times a feeling of lack of belonging in either family. It can open an entire door of risks and what-ifs. Sometimes it can fill a hole, and other times can make a hole a bit bigger. Finding family members can feel like finding the first chapters of our story. The beginning pages could be crinkled, stained, smudged, ripped in multiple pieces, and contain some illegible sentences and paragraphs. At the same time, the long-lost pages have finally been found.

Beyond the complexities and unknowns in reunions, there is comfort knowing that God can be the author of our story if we allow Him to be. We are not defined by our beginnings. Our beginnings impact us and shape us, BUT God is our potter. How even more can He shape us, mold us, and transform us. (So incredibly thankful that God created us intricately with phenomena such as neuroplasticity). We are God’s handiwork. Isaiah 64:8 states, “Yet you, LORD, are our Father. We are the clay, you are the potter; we are all the work of your hand.” He says we are His and never will he forsake us. There is reassurance and encouragement for this truth as we continue our life journey.